Fact Check

Information is available 24/7. How do you know whom to believe? News literacy programs help students sort fact from fiction.

Khadija Qanoongo, 12, says she used to believe everything she read online. Then, in sixth grade, she took a news literacy class. She learned how to determine if a website is reliable. She found out that many are not. “Now I’m very careful when I read news on the Internet,” Khadija told TFK.

BEYOND HEADLINES I.S. 303 teachers Marisol Solano and Brett Dobin encourage students to think critically about the news.

NATAKI HEWLING FOR TIME FOR KIDSKhadija goes to I.S. 303, in Brooklyn, New York. Marisol Solano teaches news literacy at the school. “When the students first come into the class, they think it’s about looking at current events and summarizing,” she says. “I tell them that news literacy is really about trying to get to the truth.”

Reading Between the Lines

Rosamaria Garces, 12, also a student at I.S. 303, says thinking critically about the news has never been more important. She has seen several fake stories posted on social media. “I think kids my age should notice more and read between the lines,” she says.

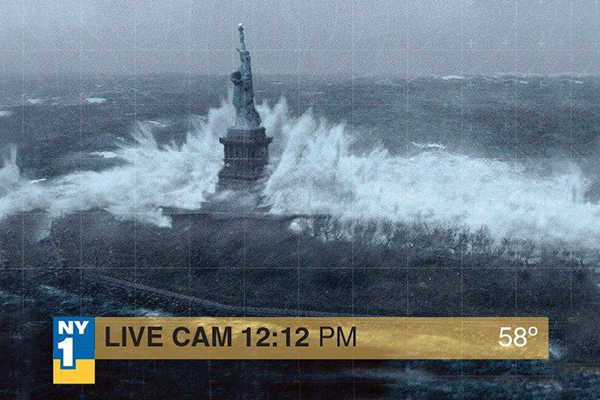

Breaking news stories offer a challenge. In 2012, just after Superstorm Sandy hit the East Coast, a dramatic photo appeared on Twitter. Many people believed it was real. But it was a fake that combined a news station logo with a scene from a movie.

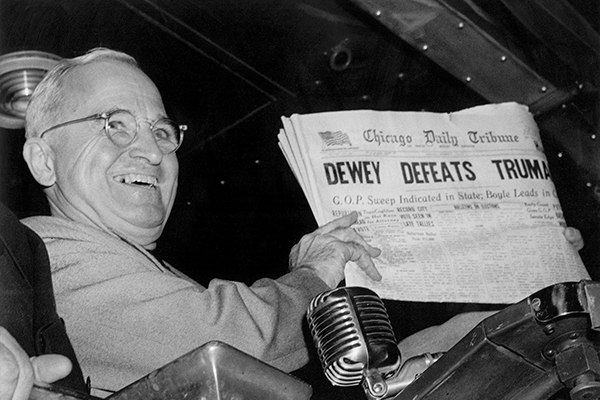

WHOOPS! In 1948, President Harry Truman holds a newspaper incorrectly announcing that his opponent, Thomas Dewey, has won the election.

BYRON ROLLINS—APAngel Gonzalez teaches news literacy at De La Salle Academy, in New York City. He pushes his students to consider where their news comes from. “We think about what is good for the body to eat, and the same applies to information,” he says. “We’re only as good as the information we consume, in terms of our ability to [know about] the world.”

Through a program called the News Literacy Project, professional journalists visit Gonzalez’s classes. They talk about what goes into producing news coverage that people can trust.

Alan Miller, a former reporter, started the program. It is now in more than 100 schools. Miller points out that anybody can post his or her views onto social media. But a story must meet a different, stricter set of standards

standard

PETER CARROLL—GETTY IMAGES

a level of quality that is considered acceptable or desirable

(noun)

Brian easily met the standard to join his school’s soccer team.

to make the front page of a major newspaper. “All information is not created equal,” he says.

PETER CARROLL—GETTY IMAGES

a level of quality that is considered acceptable or desirable

(noun)

Brian easily met the standard to join his school’s soccer team.

to make the front page of a major newspaper. “All information is not created equal,” he says.

LOOKS REAL. IS IT? After a storm hits the New York area, this photo is posted online. It shows a scene from a popular movie, not a news photo.

TWITTEROf course, news organizations make mistakes too. The day after the 1948 presidential election, the Chicago Daily Tribune famously announced that Thomas Dewey had won. In fact, he had lost.

News literacy students also learn to consider an author’s purpose. Solano tells her students to ask themselves: Is the author presenting both sides? If not, the writer’s aim may be to persuade readers. Opinion articles serve a purpose, she says. But students should be aware that the author is advocating

advocate

RICH LEGG—GETTY IMAGES

to support or argue for a cause or policy

(verb)

The lawyer advocated for his client in court.

a point of view.

RICH LEGG—GETTY IMAGES

to support or argue for a cause or policy

(verb)

The lawyer advocated for his client in court.

a point of view.

Danish Tufail, 11, has been using what he learned in news literacy to make sense of Election 2016 coverage. Someday, “we’re going to have to elect a president,” says the seventh grader at I.S. 303. “Knowing what to believe about the candidates is important.”

The date of Superstorm Sandy has been corrected in this version.

Think!

Rosamaria Garces says thinking critically about news has never been more important. Do you agree?

A Free Press

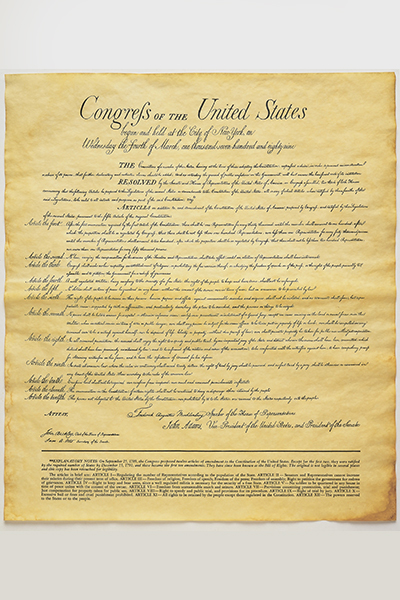

In 1791, lawmakers added 10 amendments to the U.S. Constitution. These are known as the Bill of Rights (above).

The First Amendment guarantees five freedoms for Americans. One of these is freedom of the press. Lawmakers knew that if the government could block opinions or stories, then the public would be less informed.

In some countries, the government limits what journalists can report. Writers can be punished for investigating stories that the government doesn’t like. Thomas Jefferson once wrote, “Our liberty depends on the freedom of the press.” Do you agree?