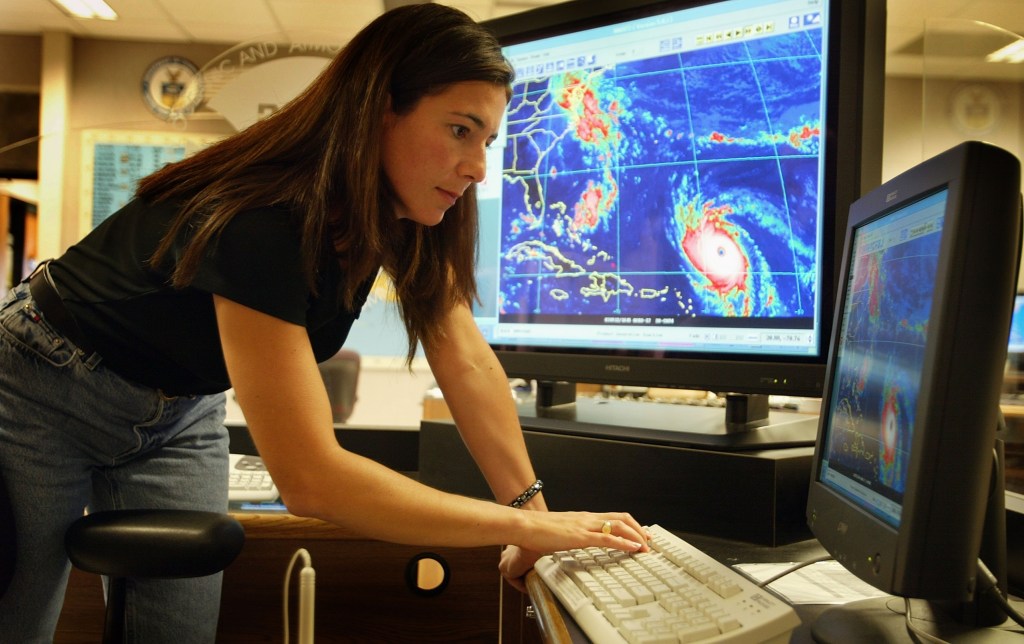

Whipping wind and hammering rain take hold of the aircraft, rattling its passengers. Stomachs drop. The radar screen goes fuzzy. This would frighten most people. But flight director Jessica Williams remains focused.

Williams is a hurricane hunter. She works for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). She and 10 to 20 other crew members fly straight into these powerful storms. In August, Williams flew into Hurricane Harvey.

She and the other scientists and meteorologists

meteorologist

JOE RAEDLE—GETTY IMAGES

an expert in the study of weather and weather forecasting

(noun)

The meteorologist studied data in order to provide the weekly weather forecast.

on board track wind speed, wind direction, air pressure, air temperature, and other data. They send it to experts on the ground who analyze it and issue warnings to people in the storm’s path.

JOE RAEDLE—GETTY IMAGES

an expert in the study of weather and weather forecasting

(noun)

The meteorologist studied data in order to provide the weekly weather forecast.

on board track wind speed, wind direction, air pressure, air temperature, and other data. They send it to experts on the ground who analyze it and issue warnings to people in the storm’s path.

NOAA’s two hurricane-hunting planes—nicknamed Kermit and Miss Piggy—are built to withstand extreme conditions. Still, the ride can be rough. “We have to make quick decisions,” Williams told TFK. “We’re busy the whole flight.”

Storm Warning

Hurricanes form over warm ocean waters. They bring heavy precipitation

precipitation

TOM CARTER—GETTY IMAGES

water that falls to the Earth as hail, mist, rain, sleet, or snow

(noun)

The thunderstorm brought heavy precipitation.

and strong winds. The eye of a hurricane is a mostly calm area at the center of a storm. The area enclosing the eye, called the eyewall, is the most dangerous part. Wind speeds there can reach more than 150 miles per hour.

TOM CARTER—GETTY IMAGES

water that falls to the Earth as hail, mist, rain, sleet, or snow

(noun)

The thunderstorm brought heavy precipitation.

and strong winds. The eye of a hurricane is a mostly calm area at the center of a storm. The area enclosing the eye, called the eyewall, is the most dangerous part. Wind speeds there can reach more than 150 miles per hour.

DAVID HALL—NOAA

DAVID HALL—NOAAFor a hurricane hunter, crossing through the eyewall is the most turbulent

turbulent

VICKI JAURON—BABYLON AND BEYOND PHOTOGRAPHY/GETTY IMAGES

unsteady

(adjective)

Choppy water made for a turbulent boat ride.

part of each eight-to-10-hour mission. The team weaves in and out of the eyewall multiple times. They map out the motion of the storm and mark the coordinates

coordinate

VICKI JAURON—BABYLON AND BEYOND PHOTOGRAPHY/GETTY IMAGES

unsteady

(adjective)

Choppy water made for a turbulent boat ride.

part of each eight-to-10-hour mission. The team weaves in and out of the eyewall multiple times. They map out the motion of the storm and mark the coordinates

coordinate

GETTY IMAGES

a set of numbers used to locate an exact position

(noun)

The team studied coordinates on the map to plan their trip.

of the storm’s center. This data informs researchers about whether the storm is getting stronger or losing steam.

GETTY IMAGES

a set of numbers used to locate an exact position

(noun)

The team studied coordinates on the map to plan their trip.

of the storm’s center. This data informs researchers about whether the storm is getting stronger or losing steam.

“We don’t know what the storm looks like until we get there,” Williams says, “so the first [flight] through a storm is always the scariest.”

But after years of hands-on practice and experience, Williams has learned to act quickly and trust her instincts. “Once I make a call, even if it’s bumpy,” she says, “I just have to hold on.”

Williams has always been fascinated by weather. As a kid growing up outside Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, she used to lie in her driveway and watch summer storms roll in. “I love all sorts of weather patterns,” she says. After earning a degree in meteorology, she served as a weather officer in the U.S. Air Force.

Williams feels the rewards of her job are well worth the challenges. “We can’t stop natural disasters—that’s out of our control,” she says. “But by studying how they work, we can help people stay safe.”