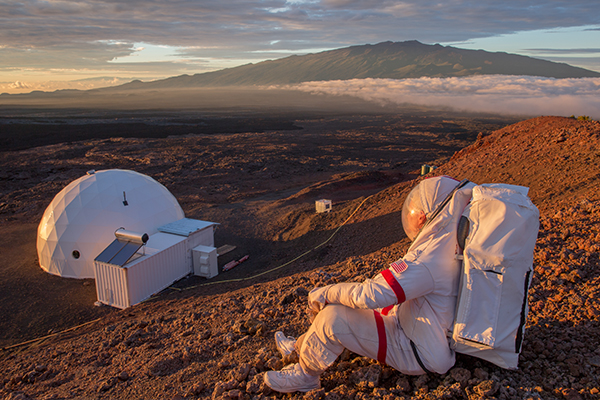

TIME’s space writer spent 24 hours inside a NASA base in Hawaii that copies conditions on the Red Planet.

Jeffrey Kluger is dressed in a space suit, just as an astronaut on Mars would be.

CASSANDRA KLOS FOR TIMEI encountered a lava tube at the end of a 10-minute walk from my Martian habitat. I had reached the top of a ridge, and as I turned my helmeted head down, I saw it. Below me was a

My time on Mars wasn’t spent on the real Mars. I was 8,200 feet up on the Mauna Loa volcano, in Hawaii. It was my good fortune that my visit lasted only 24 hours.

The HI-SEAS facility is on the Mauna Loa volcano in Hawaii. Does the site look like the Red Planet?

CASSANDRA KLOS FOR TIMEThe Road to the Red Planet

Just a few days earlier, on August 28, a team of six scientists, engineers, and astronaut hopefuls had completed a full year in the simulated Mars habitat. It is known as HI-SEAS (Hawaii Space Exploration Analog and Simulation). The “hab” features a 1,200-square-foot dome with a 424-square-foot sleeping loft. It also includes two small bathrooms, a small kitchen, and a storage area stocked with food. The facility is comanaged by NASA and the University of Hawaii.

The crew could go outside for Mars walks (officially called extravehicular activity, or EVA), but only in full-body space suits. They could communicate with Mission Control and family members, but only by e-mail or text. Their communications had to have a 20-minute, one-way delay, the length of time it takes for a message to travel between Mars and Earth. The reason for such strict rules: Scientists need to better understand how long-term, no-break space travel affects the human mind.

The loft area has six small bedrooms and a bathroom.

CASSANDRA KLOS FOR TIMEThere have been three HI-SEAS missions before this one, but none has lasted as long. Two went for four months, and one went eight. Researchers hope to gain understanding of what makes a person mentally fit for a Mars adventure. At least two years of travel would be required to send people to the Red Planet and bring them back.

“NASA needs to understand what happens with numerous teams for really long periods,” says Steve Kozlowski, a psychologist and HI-SEAS researcher. “Only then can we know what to expect from a real Mars crew.”

The Power of Pretending

My two EVAs were partly (okay, mostly) about playing spaceman. Even if my excursions were mostly for fun, the HI-SEAS teams’ EVAs are not. Team members are sent out on

Kluger, left, and Arthur Cunningham, a member of the HI-SEAS team, collect rocks.

CASSANDRA KLOS FOR TIMESimulated space travel also includes flushless, composting toilets (which you can’t avoid, even during a one-day stay) and chilly, two-minute showers (which I could—and did—spare myself).

None of those minor hardships compares with what would be the monumental achievement of getting people on Mars. My 24 hours on fake Mars were nothing next to the year the HI-SEAS crew completed. The work being done in a hab in Hawaii brings that very big achievement an important step closer.