Wild animals roamed

roam

FEIFEI CUL-PAOLUZZO/GETTY IMAGES

to travel through a large area

(verb)

Sheep roamed the meadow.

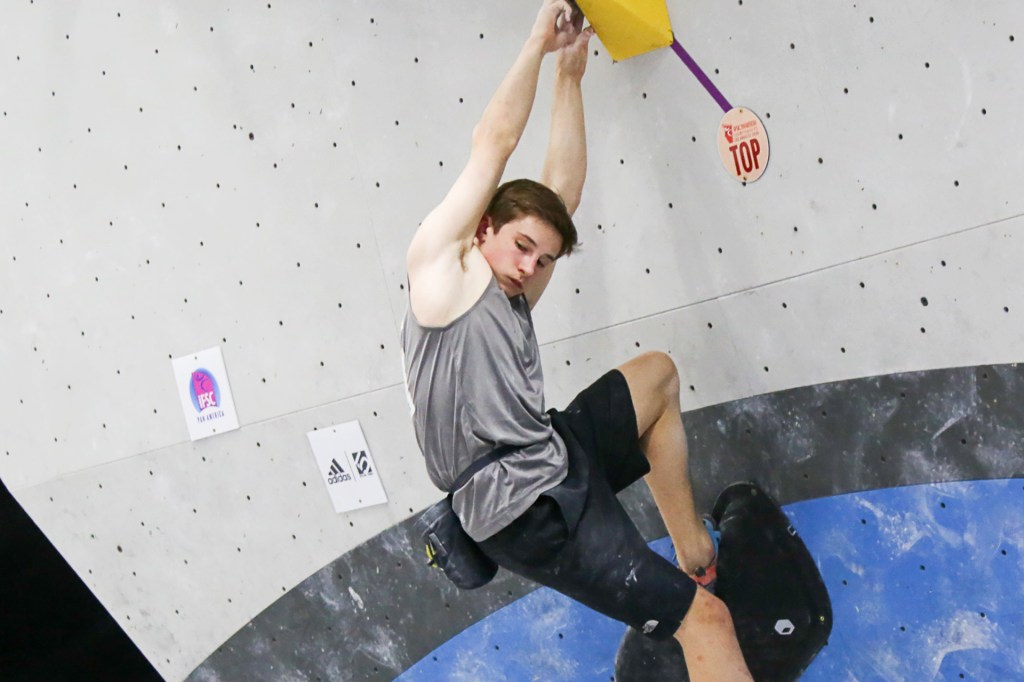

at night. But Rose Peter and the 19 other children she was with still slept outside. In the daylight, they walked. “One week,” Rose tells me when I ask how long the trip took. She says they set off alone from South Sudan to Kenya. (Their parents came later.) That was in 2014. Rose has lived at Kakuma refugee camp ever since.

FEIFEI CUL-PAOLUZZO/GETTY IMAGES

to travel through a large area

(verb)

Sheep roamed the meadow.

at night. But Rose Peter and the 19 other children she was with still slept outside. In the daylight, they walked. “One week,” Rose tells me when I ask how long the trip took. She says they set off alone from South Sudan to Kenya. (Their parents came later.) That was in 2014. Rose has lived at Kakuma refugee camp ever since.

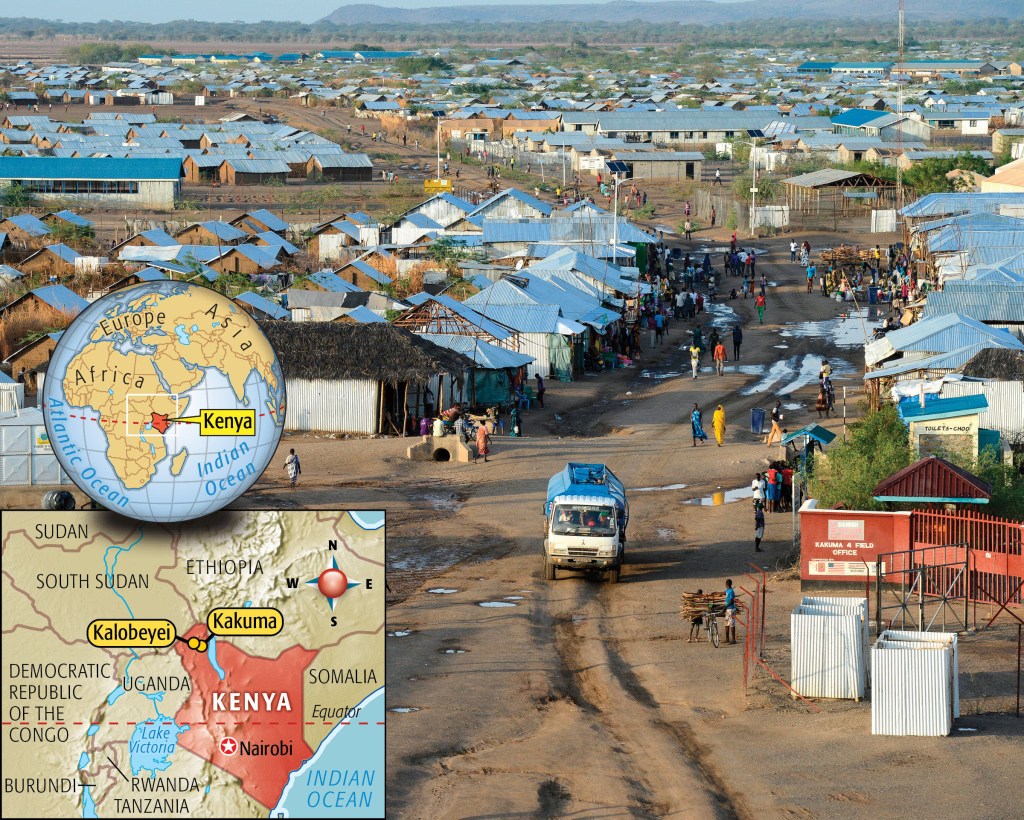

Kakuma refugee camp (above) and Kalobeyei settlement are in northwestern Kenya. They are home to nearly 186,000 refugees from 19 countries.

JOERG BOETHLING—ALAMY PHOTO STOCK. MAPS BY JOE LEMONNIER FOR TIME FOR KIDS“There was a war in my country,” Rose says. In fact, civil war still rages in South Sudan. “I am hoping that after I finish school, my life will be changed completely,” Rose says.

Rose, 18, is a refugee. A refugee is a person who has fled his or her country due to war. Other reasons can also play a role. A 1951 United Nations agreement explains refugees’ rights. One is the right to education for children.

In March, I visited Kakuma camp and Kalobeyei settlement

settlement

MARKUS DANIEL/GETTY IMAGES

a place where people have come to live

(noun)

During her vacation to Peru, Ada visited the remains of an ancient settlement called Machu Picchu.

. I went with UNICEF, the United Nations Children’s Fund. I wanted to learn what life is like for kids who go to school in refugee camps.

MARKUS DANIEL/GETTY IMAGES

a place where people have come to live

(noun)

During her vacation to Peru, Ada visited the remains of an ancient settlement called Machu Picchu.

. I went with UNICEF, the United Nations Children’s Fund. I wanted to learn what life is like for kids who go to school in refugee camps.

Visiting Classrooms

At Mogadishu Primary School, children crowd into a dirt courtyard. Kids sip porridge

porridge

SEAN JUSTICE/GETTY

a soft food made by cooking grains in milk or water until thick

(noun)

Darryl likes to eat porridge for breakfast.

from plastic mugs. A worker stands over a bubbling pot of beans and corn. This will be lunch for Mogadishu’s 21 teachers.

SEAN JUSTICE/GETTY

a soft food made by cooking grains in milk or water until thick

(noun)

Darryl likes to eat porridge for breakfast.

from plastic mugs. A worker stands over a bubbling pot of beans and corn. This will be lunch for Mogadishu’s 21 teachers.

I’m greeted by teacher Pascal Lukosi. “Enrollment is moving higher and higher,” he says. The school has 2,815 students. That is one teacher for every 134 students.

In Kakuma, it is common for students of many ages to learn together in a single classroom.

RODGER BOSCH FOR UNICEF USAFacing Challenges

Kakuma has 21 primary schools. Bhar-El-Naam is one of two just for girls. In the afternoon, I meet with five students. I ask what they normally do after class.

“I fetch water and wash utensils and clothes,” says Njema Nadai Ben, 12. Homes do not have running water. Refugees fill up at wells called boreholes.

What about homework? “We don’t have lights to read at night,” says Rachel Akol Dau, 17. She does homework by firelight.

Kalobeyei Friends School has nearly 6,000 learners. They cram into unfinished classrooms. “We are just sitting on dirt” on a mat, says Jonathan Kalo Ndoyan, 17. Each textbook is shared by 18 students.

Children at Kalobeyei Friends School take a water break. The school has almost 6,000 kids.

JAIME JOYCE FOR TIME FOR KIDSAt Morneau Shepell Secondary School for Girls, I meet Nawadhir Nasradin, 16. She recites a poem. It ends with these words: “Education empowers.” It is my last day in Kakuma. I picture Rose, whom I met on my first day. She wants to be a doctor. She dreams of peace in South Sudan. When we met, I asked what school she attended. It’s called Hope.

How You Can Help

Worldwide, there are nearly 23 million refugees. More than half are children. UNICEF works to protect them.

UNICEF kits (pictured below) are a way to make sure refugee children get an education. Kits contain basic school supplies. They include books, pencils, and blocks for counting.

“Whenever they come in contact with these kits, they are very happy,” says Songot Paul. He is head teacher at Kalobeyei Friends. “They are motivated to learn even more.”

Would you like to help refugee kids? With an adult, go to unicefusa.org/tfk to donate. A little goes a long way: $14 is enough for a set of 40 notebooks, 40 slates, and 80 pencils. You and your school can also help by taking part in UNICEF’s Kid Power program. Visit unicefkidpower.org.

Jaime Joyce is executive editor of TIME for Kids. She went to Kenya to report this story. The article is made possible by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.